There’s a new DORA report out from Google, but it’s not the usual DevOps one we’ve come to expect – this one is entirely focused on the state of AI-assisted software development.

That’s not too surprising, straight up DevOps is last decade’s news – Gene Kim rebranded the DevOps Enterprise Summit and is publishing vibe coding books, the DevOps OGs like Patrick Debois and John Willis have been focusing on AI building, and so it makes sense that the DORA crew are also poking in that direction.

A lot of the shift in DevOps in recent years has been towards focusing on developer productivity. Whether that’s the rise of platforms to take burden and complexity away from devs, to Nicole Forsgren’s new SPACE metrics that extended her previous Accelerate/DORA metrics that were focused just on software delivery, everyone is keenly aware that unlocking the developers’ ability to create is important.

Companies I work with are really prioritizing that. At ServiceNow, they got Windsurf licenses for all and report a 10% productivity boost from it. And just “we have some AI” isn’t enough, Meta just cut one of their major AI teams because they had “gotten too bureaucratic” and slow so they wanted to move people to a newer team where they could get more done. So companies are taking developer productivity very seriously and spending real money and making big changes to get it.

Understanding Your Software Delivery Performance

As you read the report, you’ll notice that large chunks of it are NOT about AI directly. This first chapter, for example, recaps the important areas from previous DORA reports. It talks about metrics for software delivery and characterizes kinds of teams you see in the wild and their clusters of function and dysfunction. You don’t really get to AI till page 23.

Is this “AI-washing”? If so, it’s justified. People want “AI” to be the solution when they don’t understand their problem, or how to measure whether their problem is solved – AI can help with software engineering and DevOps but it does nothing to change the fundamental nature of any of it, so if you don’t understand the non-AI basics, if you’re handed AI to loose on your company you may as well be an armed toddler.

AI Adoption and Use

The report has good stats that dig deeper than news reports – while 90% of people are “using AI”, in general they use it maybe 1-2 hours out of their day and don’t go to it first all the time.

The thing I found the most surprising was what people were using it for. In my experience folks are using AI for the lighter work more often than actually writing code, but their research showed writing code was by far the most common use case (60%) and stuff like internal communication the least common task (48%) (outside calendar management at 25%, but the tools for that are terrible IMO).

Chatbots and IDEs are the vast majority of how people interact with AI still, integrated tool platforms only have 18% traction.

People do in general believe they’re being more productive from using AI, by a wide margin, and also believe their code quality has gone up! Pure vibe coding makes terrible quality code, I believe this is because how real coders are using AI is more thoughtful than just “write this for me.” And this is borne out in their trust metrics – most people do NOT trust AI output. 76% of respondents trust AI somewhat, a little, or not at all – despite 84% believing it has increased their productivity.

I think that’s super healthy – you should not trust AI output, but if you keep that in mind, it lets you use it and be more productive. You just have to double check and not expect magic. Consider that ServiceNow article I linked above about their Windsurf adoption, it’s not reastic to think AI is going to give you orders of magnitude of coding productivity increase – 10% is great though, more of an improvement than most other things you can do!

AI and Key Outcomes

That leads us into the meatier portion of the report, which is taking the research past “what people think” and trying to correlate real outcomes to these factors. Which is a little ticky, because developer morale is a part of what contributes to delivery and there may be a “placebo factor” where believing AI tools are making you better, makes you better whether or not the tool is contributing!

What they found is that while AI use does really improve individual effectiveness, code quality, and valuable work, it doesn’t help with friction and burnout, and has a significant negative effect on software delivery instability.

So what do we make of increased software delivery instability when we think we’re generating more and better code? And we think the org performance is still doing better? The report doesn’t know either.

My theory is similar to the answer to “why doesn’t everyone run multi-region systems when AWS us-east goes down from time to time?” Just to refresh you on the answer to that one, “it’s more expensive to do it right than to have an outage from time to time.” If you can cram more code down the pipe, you get more changes and therefore more instability. But just like companies gave up on shipping bug-free code long ago, some degree of failure with the tradeoff of shipping more stuff is a net financial win.

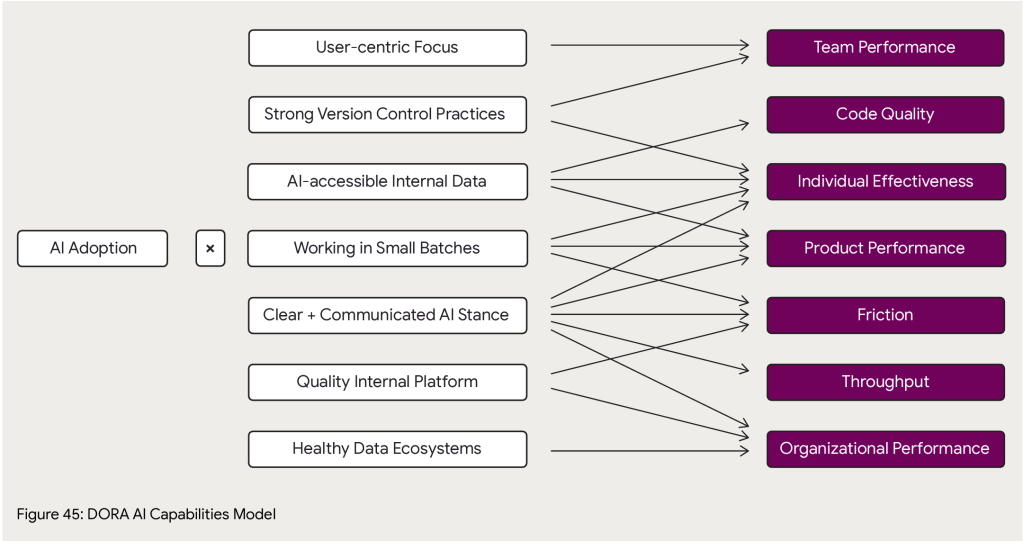

AI Capabilities Model

The reason I love DORA is they go deep and try to establish correlation of AI adoption best practices to outcomes. At page 49 is their big new framework for analysis of AI impact on an org. Here’s what they have so far on how specific practices correlate to specific outcomes, with caveats that it’ll take another year of data to know for sure (though AI innovation cycles are month by month, I hope they’ll find a way to get more data more quickly than a yearly cadence).

Platform Engineering

The report then takes another turn back to earlier DORA topics and talks about platform engineering, the benefits, and how to not suck at it.

For those who are unclear on that, you get wins from a platform that is user centric. So many organizations don’t – or deliberately mis- – understand that. You could call all the old centralized IT solutions from previous decades a “platform” – Tivoli, HP WhateverCenter, and so on – but they were universally hateful and got in the way of progress in the name of optimizing the work of some commodity team behind a ticket barrier. (I’ll be honest, there’s a lot of that at my current employer.)

I’m going to go a step farther than the report – if you don’t have a product manager guidlign your platform based on its end users’ needs, your platform is not really a platform, it’s a terrible efficiency play that is penny wise but pound foolish. Fight me.

Anyway, they then say “platforms, you know, it’s the place you can plug in AI.” Which is fine but a little basic.

Value Stream Management

Is important. The premise here is that given the basic premise of value flow (if you don’t know about lean and value streams and stuff, I’ve got a LinkedIn Learning course for you: DevOps Foundations: Lean and Agile), systems thinking dictates that if you accelerate pieces in your workflow you can actually harm your overall throughput, so major changes mean you need to revisit the overall value stream to make sure it’s still the right flow, and measure so you understand how speeding up pieces (like oh say making code) affects other pieces (like oh say release stability).

They find that AI adoption gets you a lot more net benefit in organizations that understand and engineer their value stream.

The AI Mirror

This section tries to address the mix of benefits and detriments we’ve already talked about with AI. It basically just says hey, rethink how you do stuff and see if you can use AI in a more targeted way to improve the bad pieces, so for software delivery try using it more for code reviews and in your delivery pipelines. It’s fine but pretty handwavey.

That’s understandable, I don’t think anyone’s meaningfully figured out how to bring AI to bear on the post-code writing part of the software delivery pipeline. There’s a bunch of hopefuls in this space but everything I’ve kicked the tires on seems still pretty sketch.

Metrics Frameworks

You need metrics to figure out if what you’re doing is helping or not. They mention frameworks like SPACE, DevEx, HEART, and DORA’s software delivery metrics, and note that you should be looking at developer experience, product excellence, and organizational effectiveness. “Does AI change this?” Maybe, probably not as much as you think.

And that’s the end at page 96, there’s 50 pages of credits and references and data and methodology if you want to get into it.

Those last 4 chapters feel more like an appendix, they don’t really flow with the rest of the report. The AI methodology talks about things to do specifically boost your AI capabilities (Clear and communicated AI stance… Working in small batches) which somewhat overlap (Quality internal platforms, User-centric focus) with these later chapters but to a degree don’t. If value stream management is shown to improve your AI outcomes then – why’s it not in the capability model?

I assume the answer is, to a degree, “Hey man this is a work in progress” which is fair enough.

Conclusion

I find two major benefits from reports like this, and judge their success based on how well they achieve them.

- Showing clear benefits of something, so you can use it to influence others to adopt it. This report does very well there. One of my complaints about the DORA reports is that in recent years they’d become more about the “next big thing” than about demonstrating the clear benefits of core DevOps practices, so I’d often go back and refer to older reports instead of the newer ones. But here – are people getting benefit from AI? Yes, and here’s what, and here’s what not. Very cleaar and well supported.

- Telling you how to best go about doing something, so you can adopt it more effectively. The report also does well here, with the caveat of “so much of this is still emerging and moving at hyperspeed that it’s hard to know.” They’ve identified practices within AI adoption and in the larger organization that are correlated to better outcomes, and that’s great.

And I do like the mix of old and new in this report. You have to wave the new shiny at people to get them to pay attention, but in the end there are core truths about running a company and a technology organization within a company – value streams, metrics, developer experience, release cadence and quality – that AI or any new silver bullet may change the implementation of, but does not change fundamentally, and it’s a good reminder that adopting sound business basics is the best way to take advantage of any new opportunity, in this case AI.

TL;DR – Good report, use it to learn how people are benefitting from AI and to understand specific things you can do to make your organization benefit the most from it!