Naturally, Ops is the Predator and Dev is Ahnuld. We Ops folks are individually fearsome and have cool technology. But the Devs have the numbers on us, and despite speaking somewhat incoherently, win in the end.

Tag Archives: DevOps

DevOps: It’s Not Chef And Puppet

There’s a discussion on the devops Google group about how people are increasingly defining DevOps as “chef and/or puppet users” and that all DevOps is, is using one of these tools. This is both incorrect and ignorant.

Chef and puppet are individual tools that you can use to implement specific parts of an overall DevOps strategy if you want to use them – but that’s it. They are fine tools, but do not “solve DevOps” for you, nor are they even the only correct thing to do within their provisioning niche. (One recent poster got raked over the coals for insisting that he wanted to do things a different way than use these tools…)

This confusion isn’t unexpected, people often don’t want to think too deeply about a new idea and just want the silver bullet. Let’s take a relevant analogy.

Agile. I see a lot of people implement Scrum blindly with no real understanding of anything in the Agile Manifesto, and then religiously defend every one of Scrum’s default implementation details regardless of its suitability to their environment. Although that’s better than those that even half ass it more and just say “we’ve gone to our devs coding in sprints now, we must be agile, woot!” Of course they didn’t set up any of the guard rails, and use it as an exclude to eliminate architecture, design, and project planning, and are confused when colossal failure results.

DevOps. “You must use chef or puppet, that is DevOps, now let’s spend the rest of our time fighting over which is better!” That’s really equivalent to the lowest level of sophistication there in Agile. It’s human nature, there are people that can’t/don’t want to engage in higher order thought about problems, they want to grab and go. I kinda wish we could come up with a little bit more of a playbook, like Scrum is for Agile, where at least someone who doesn’t like to think will have a little more guidance about what a bundle of best practices *might* look like, at least it gives hints about what to do outside the world of yum repos. Maybe Gene Kim/John Willis/etc’s new DevOps Cookbook coming out soon(?) will help with that.

My own personal stab at “What is DevOps” tries to divide up principles, methods, and practices and uses agile as the analogy to show how you have to treat it. Understand the principles, establish a method, choose practices. If you start by grabbing a single practice, it might make something better – but it also might make something worse.

Back at NI, the UNIX group established cfengine management of our Web boxes. But they didn’t want us, the Web Ops group, to use it, on the grounds that it would be work and a hassle. But then if we installed software that needed, say, an init script (or really anything outside of /opt) they would freak out because their lovely configurations were out of sync and yell at us. Our response was of course “these servers are here to, you know, run software, not just happily hum along in silence.” Automation tools can make things much worse, not just better.

At this week’s Agile Austin DevOps SIG, we had ~30 folks doing openspaces, and I saw some of this. “I have this problem.” “You can do that in chef or puppet!” “Really?” “Well… I mean, you could implement it yourself… Kinda using data bags or something…” “So when you say I can implement it in chef, you’re saying that in the same sense as ‘I could implement it in Java?'” “Uh… yeah.” “Thanks kid, you’ve been a big help.”

If someone has a systems problem, and you say that the answer to that problem is “chef” or “puppet,” you understand neither the problem nor the tools. It’s “when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail – and beyond that, every part of a construction job should be solved by nailing shit together.”

We also do need to circle back up and do a better job of defining DevOps. We backed off that early on, and as a result we have people as notable as Adrian Cockroft saying “What’s DevOps? I see a bunch of conflicting blog posts, whatever, I’ll coin my own *Ops term.” That’s on us for not getting our act together. I have yet to see a good concise DevOps definition that is unique if you remove the word DevOps and insert something else (“DevOps helps you bring value to software! DevOps is about delivering a service to a customer!” s/DevOps/100 other things/).

At DevOpsDays, some folks contended that some folks “get” DevOps and others don’t and we should leave them to their shame and just do our work. But I feel like we have some responsibility to the industry in general, so it’s not just “the elite people doing the elite things.” But everyone agreed the tool focus is getting too much – John Willis even proposed a moratorium on chef/puppet/tooling talks at DevOpsDays Mountain View because people are deviating from the real point of DevOps in favor of the knickknacks too much.

Filed under DevOps

Monitorin’ Ain’t Easy

The DevOps space has been aglow with discussion about monitoring. Monitoring, much like pimping, is not easy. Everyone does it, but few do it well.

The DevOps space has been aglow with discussion about monitoring. Monitoring, much like pimping, is not easy. Everyone does it, but few do it well.

Luckily, here on the agile admin we are known for keeping our pimp hands strong, especially when it comes to monitoring. So let’s talk about monitoring, and how to use it to keep your systems in line and giving you your money!

In November, I posted about why your monitoring is lying to you. It turns out that this is part of a DevOps-wide frenzy of attention to monitoring.

John Vincent (@lusis) started it with his Why Monitoring Sucks blog post, which has morphed into a monitoringsucks github project to catalog monitoring tools and needs. Mainstream monitoring hasn’t changed in oh like 10 years but the world of computing certainly has, so there’s a gap appearing. This refrain was quickly picked up by others (Monitoring Sucks. Do Something About It.) There was a Monitoring Sucks panel at SCALE last week and there’s even a #monitoringsucks hashtag.

Patrick Debois (@patrickdebois) has helped step into the gap with his series of “Monitoring Wonderland” articles where he’s rounding up all kinds of tools. Check them out…

However it just shows how fragmented and confusing the space is. It also focuses almost completely on the open source side – I love open source and all but sometimes you have to pay for something. Though the “big ol’ suite” approach from the HP/IBM/CA lot makes me scream and flee, there’s definitely options worth paying for.

Today we had a local DevOps meetup here in Austin where we discussed monitoring. It showed how fragmented the current state is. And we met some other folks from a “real” engineering company, like NI, and it brought to mind how crap IT type monitoring is when compared to engineering monitoring in terms of sophistication. IT monitoring usually has better interfaces and alerting, but IT monitoring products are very proud when they have “line graphs!” or the holy grail, “histograms!” Engineering monitoring systems have algorithms where they can figure out the difference between a real problem and a monitoring problem. They apply advanced algorithms when looking at incoming metrics (hint: signal processing). When is anyone in IT world who’s all delirious about how cool “metrics” going to figure out some math above the community college level?

To me, the biggest gap especially in cloud land – partially being addressed by New Relic and Boundary – in the space is agent based real user monitoring. I want to know each user and incoming/outgoing transaction, not at the “tcpdump” level but at the meaningful level. And I don’t want to have to count on the app to log it – besides the fact that devs are notoriously shitful loggers, there are so many cases where something goes wrong – if tomcat’s down, it’s not logging, but requests are still coming in… Synthetic monitoring and app metrics are good but they tend to not answer most of the really hard questions we get with cloud apps.

We did a big APM (application performance management) tool eval at NI, and got a good idea of the strengths and weaknesses of the many approaches. You end up wanting many/all of them really. Pulling box metrics via SNMP or agents, hitting URLs via synthetic monitors locally or across the Internet, passive network based real user monitoring, deep dive metric gathering (Opnet/AppDynamics/New Relic/etc.)… We’ll post more about our thoughts on all these (especially Peco, who led that eval and is now working for an APM company!).

Your thoughts on monitoring? Hit me!

Filed under DevOps

Service Delivery Best Practices?

So… DevOps. DevOps vs NoOps has been making the rounds lately. At Bazaarvoice we are spawning a bunch of decentralized teams not using that nasty centralized ops team, but wanting to do it all themselves. This led me to contemplate how to express the things that Operations does in a way that turns them into developer requirements?

Because to be honest a lot of our communication in the Ops world is incestuous. If one were to point a developer (or worse, a product manager) at the venerable infrastructures.org site, they’d immediately poop themselves and flee. It’s a laundry list of crap for neckbeards, but spends no time on “why do you want this?” “What value will this bring to your customer?”

So for the “NoOps” crowd who want to do ops themselves – what’s an effective way to state these needs? I took previous work – ideas from the pretty comprehensive but waterfally “Systems Development Framework” Peco and I did for NI, Chris from Bazaarvoice’s existing DevOps work – and here’s a cut. I’d love feedback. The goal is to have a small discrete set of areas (5-7), with a small discrete set (5-7) of “most important” items – most importantly, stated in a way so that people understand that these aren’t “annoying things some ops guy wants me to do instead of writing 3l33t code” but instead stated as they should be, customer facing requirements like any other. They could then be each broken into subsidiary more specific user stories (probably a whole lot of them, to be honest) but these could stand in as “epics” or “pillars” for making your Web thing work right.

Service Delivery Best Practices

Availability

- I will make my service highly available, so that customers can use it constantly without issues

- I will know about any problems with my service’s delivery to customers

- I can restore my service quickly from any disaster or loss

- I can make my data resistant to corruption from runtime issues

- I will test my service under routine disruption to make it rugged and understand its failure modes

Performance

- I know how all parts of the product perform and can measure performance against a customer SLA

- I can run my application and its data globally, to serve our global customer base

- I will test my application’s performance and I know my app’s limitations before it reaches them

Support

- I will make my application supportable by the entire organization now and in the future

- I know what every user hitting my service did

- I know who has access to my code and data and release mechanism and what they did

- I can account for all my servers, apps, users, and data

- I can determine the root cause of issues with my service quickly

- I can predict the costs and requirements of my service ahead of time enough that it is never a limiter

- I will understand the communication needs of customers and the organization and will make them aware of all upgrades and downtime

- I can handle incidents large and small with my services effectively

Security

- I will make every service secure

- I understand Web application vulnerabilities and will design and code my services to not be subject to them

- I will test my services to be able to prove to customers that they are secure

- I will make my data appropriately private and secure against theft and tampering

- I will understand the requirements of security auditors and expectations of customers regarding the security of our services

Deployment

- I can get code to production quickly and safely

- I can deploy code in the middle of the day with no downtime or customer impact

- I can pilot functionality to limited sets of users

- I will make it easy for other teams to develop apps integrated with mine

Also to capture that everyone starting out can’t and shouldn’t do all of this… We struggled over whether these were “Goals” or “Best Practices” or what… On the one hand you should only put in e.g. “as much security as you need” but on the other hand there’s value in understanding the optimal condition.

Filed under DevOps

Awesome Austin Tech Meetups

Austin is such a great place to be a techie.

- The Austin Cloud User Group (I help run it) meets every third Tuesday evening, and we’ve ben having 50+ people come in to check out some awesome stuff. Next meeting Feb 21 on Puppet, hosted by Pervasive.

- The Agile Austin DevOps SIG meets fourth Wednesdays, we had our meeting today and had about 20 attendees, hosted by CA/Hyperformix. I also help run that one.

- The Austin Big Data User Group is back meeting – next one is tomorrow night! Hosted by Bazaarvoice.

- The Austin OWASP chapter is one of the biggest and most active in the country, and also meets monthly, hosted by National Instruments. Fellow Agile Admin James Wickett helps run that group.

- The Cloud Security Alliance, Austin chapter is just getting started but has a lot of momentum and we’re coordinating with them from the ACUG and OWASP sides. Their first meeting is tonight, come out!

There are others but those are my favorites and therefore the coolest by definition.

There’s also cool events coming up you should keep an eye out for.

- DevOpsDays Austin, Apr 2-3, hosted by National Instruments, and this’ll be big! Patrick Debois and the whole crew of DevOps illuminati will be here. Now taking sponsors and speakers! Register now!

- AppSec USA 2012, Oct 23-26 – Austin OWASP kicks so much ass with LASCON that the annual OWASP convention is coming here to Austin this year!

- South by Southwest Interactive, March 9-13 – quickly becoming theWeb conference in the flyover states :-). Lots of stuff happens during it, like:

- Austin Cloud/DevOps party courtesy GeekAustin (ACUG is a community sponsor). March 10.

- CloudCamp – Dave Nielsen will be bringing a CloudCamp to Austin again this year during SXSWi. Details TBD, sounding like Mar 11 maybe.

- The Cloud Security Alliance and ACUG are hoping to put together an Austin cloud conference, too. Maybe early 2013.

Filed under Cloud, Conferences, DevOps

Why Your Testing Is Lying To You

As a follow-on to Why Your Monitoring Is Lying To You. How is it that you can have an application go through a whole test phase, with two-day-long load tests, and have surprising errors when you go to production? Well, here’s how… The same application I describe in the case study part of the monitoring article slipped through testing as well and almost went live with some issues. How, oh how could this happen…

I Didn’t See Any Errors!

Our developers quite reasonably said “But we’ve been developing and using this app in dev and test for months and haven’t seen this problem!” But consider the effects at work in But, You See, Your Other Customers Are Dumber Than We Are. There are a variety of levels of effect that prevent you from seeing intermittent problems, and confirmation bias ends up taking care of the rest.

The only fix here is rigor. If you hit your application and test and it errors, you can’t just ignore it. “I hit reload, it worked. Maybe they were redeploying. On with life!” Maybe it’s your layer, maybe it’s another layer, it doesn’t matter, you have to log that as a bug and follow up and not just cancel the bug as “not reproducible” if you don’t see it yourself in 5 minutes of trying. Devs sometimes get frustrated with us when we won’t let up on occurrences of transient errors, but if you don’t know why they happened and haven’t done anything to fix it, then it’s just a matter of time before it happens again, right?

We have a strict policy that every error is a bug, and if the error wasn’t detected it is multiple bugs – a bug with the monitoring, a bug with the testing, etc. If there was an error but “you don’t know why” – you aren’t logging enough or don’t have appropriate tools in place, and THAT’s a bug.

Our Load Test/Automated Tests Didn’t See Any Errors!

I’ll be honest, we don’t have much in the way of automated testing in place. So there’s that. But we have long load tests we run. “If there are intermittent failures they would have turned up over a two day load test right?” Well, not so fast. How confident are you this error is visible to and detected by your load test? I have seen MANY load test results in my lifetime where someone was happily measuring the response time of what turned out to be 500 errors. “Man, my app is a lot faster this time! The numbers look great! Wait… It’s not even deployed. I hit it manually and I get a Tomcat page.”

Often we build deliberate “lies” into our software. We throw “pretty” error pages that aren’t basic errors. We are trying not to leak information to customers so we bowderlize failures on the front end. We retry maniacally in the face of failed connections, but don’t log it. We have to use constrained sets of return codes because the client consuming our services (like, say, Silverlight) is lobotomized and doesn’t savvy HTTP 401 or other such fancy schmancy codes.

Be careful that load tests and automated tests are correctly interpreting responses. Look at your responses in Fiddler – we had what looked to the eye to be a 401 page that was actually passing back a 200 HTTP return code.

The best fix to this is test driven development. Run the tests first so you see them fail, then write the code so you see them work! Tests are code, and if you just write them on your working code then you’re not really sure if they’ll fail if somethings bad!

Fault Testing

Also, you need to perform positive and negative fault testing. Test failures end to end, including monitoring and logging and scaling and other management stuff. At the far end of this you have the cool if a little crazy Chaos Monkey. Most of us aren’t ready or willing to jack up our production systems regularly, but you should at least do it in test and verify both that things work when they should and that they fail and you get proper notification and information if they do.

Try this. Have someone Chaos Monkey you by turning off something random – a database, making a file system read only, a back end Web service call. If you have redundancy built in to counter this, great, try it with one and see the failover, but then have them break “all of it” to provoke a failure. Do you see the failure and get alerted? More importantly, do you have enough information to tell what they broke? “One of the four databases we connect to” is NOT an adequate answer. Have someone break it, send you all the available logs and info, and if you can’t immediately pinpoint the problem, fix that.

How Complex Systems Fail, Invisibly

In the end, a lot of this boils down to How Complex Systems Fail. You can have failures at multiple levels – and not really failures, just assumptions – that stack on top of each other to both generate failures and prevent you from easily detecting those failures.

Also consider that you should be able to see those “short of failure” errors. If you’re failing over, or retrying, or whatnot – well it’s great that you’re not down, but don’t you think you should know if you’re having to fail over 100x more this week? Log it and turn it into a metric. On our corporate Web site, there’s hundreds of thousands of Web pages, so a certain level of 404s is expected. We don’t alert anyone on a 404. But we do metricize it and trend it and take notice if the number spikes up (or down – where’d all that bad content go?).

Whoelsale failures are easy to detect and mitigate. It’s the mini-failures, or things that someone would argue are not a failure, on a given level that line up with the same kinds of things on all the other layers and those lined up holes start letting problems slip through.

http://www.codinghorror.com/blog/2011/04/working-with-the-chaos-monkey.html

Filed under DevOps

Why Your Monitoring Is Lying To You

In my Design for Failure article, I mentioned how many of the common techniques we use to allegedly detect failure really don’t. This time, we’ll discuss your monitoring and why it is lying to you.

Well, you have some monitoring, don’t you, couldn’t it tell you if an application is down? Obviously not if you are just doing old SNMP/box level monitoring, but you’re all DevOps and you know you have to monitor the applications because that’s what counts. But even then, there are common antipatterns to be aware of.

Synthetic Monitoring

Dirty secret time, most application monitoring is “synthetic,” which means it hits a specific URL or set of URLs once in a while, often 5-10 minutes apart. Also, since there are a lot of transient failures out there on the Internet, most ops groups have their monitors set where they have to see 2-5 consecutive failures – because ops teams don’t like being woken up at 3 AM because an application hiccuped once (or the Internet hiccuped on the way to the application). If the problem happens on only 1 of every 20 hits, and you have to see three errors in a row to alert, then I’ll leave it to your primary school math skills to determine how likely it is you’ll catch the problem.

You can improve on this a little bit, but in the end synthetic monitoring is mainly useful for coarse uptime checking and performance trending.

Metric Monitoring

OK, so synthetic monitoring is only good for rough up/down stuff, but what about my metric monitoring? Maybe I have a spiffier tool that is continuously pulling metrics from Web servers or apps that should give me more of a continuous look. Hits per second over the last five minutes; current database space, etc.

Well, I have noticed that metrics monitors, with startling regularity, don’t really tell you if something is up or down, especially historically. If you pull current database space and the database is down, you’d think there would be a big nasty gap in your chart but many tools don’t do that – either they report the last value seen, or if it’s a timing report it happily reports you timing of errors. Unless you go to the trouble to say “if the thing is down, set a value of 0 or +infinity or something” then you can sometimes have a failure, then go back and look at your historical graphs and see no sign there’s anything wrong.

Log Monitoring

Well surely your app developers are logging if there’s a failure, right? Unfortunately logging is a bit of an art, and the simple statement “You should log the overall success or failure of each hit to your app, and you should log failures on any external dependency” can be… reinterpreted in many ways. Developers sometimes don’t log all the right things, or even decide to suppress certain logs.

You should always log everything. Log it at a lower log level, like INFO, if it’s routine, but then at least it can be reviewed if needed and can be turned into a metric for trending via tools like Splunk. My rules are simple:

- Log the start and end of each hit – are you telling the client success or failure? Don’t rely on the Web server log.

- Log every single hit to an external dependency at INFO

- Log every transient failure at WARN

- Log every error at ERROR

Real User Monitoring

Ah, this is more like it. The alleged Holy Grail of monitoring is real user monitoring, where you passively look at the transactions coming in and out and log them. Well, on the one hand, you don’t have to rely on the developers to log, you can log despite them. But you don’t get as much insight as you’d think. If the output from the app isn’t detectable as an error, then the monitoring doesn’t help. A surprising amount of the time, failures are not thrown as a 500 or other expected error code. And checking for content within a payload is often fragile.

Also, RUM tools tend to be network sniffer based, which don’t work well in the cloud or in many network topologies. And you get so much data, that it can be hard to find the real problems without spending a lot of time on it.

No, Really – One Real World Example

We had a problem just this week that managed to successfully slip through all our layers of monitoring – luckily, our keen eyes caught it in preproduction. We had been planning a bit app release and had been setting up monitoring for it. It seemed like everything was going fine. But then the back end databases (SQL Azure in this case) had a pretty long string of failures for about 10 minutes, which brought our attention to the issue. As I looked into it, I realized that it was very likely we would have seen smaller spates of SQL Azure connection issues and thus application outage before – why hadn’t we? I investigated.

We don’t have any good cloud-compliant real user monitoring in place yet. And the app was throwing a 200 http code on an error (the error page displayed said 401, but the actual http code was 200) so many of our synthetic monitors were fooled. Plus, the problem was usually occasional enough that hitting once every 10 minutes from Cloudkick didn’t detect it. We fixed that bad status code, and looked at our database monitors. “I know we have monitors directly on the databases, why aren’t those firing?”

Our database metric monitors through Cloudkick, I was surprised to see, had lovely normal looking graphs after the outage.I provoked another outage in test to see, and sure enough, though the monitors ‘went red,’ for some reason they were still providing what seemed to Cloudkick like legitimate data points, and once the monitors “went green,” nothing about any of the metric graphs indicated anything unusual! In other words, the historical graphs had legitimate looking data and did not reveal the outage. That’s a big problem. So we worked on those monitors.

I still wanted to know if this had been happening. “We use Splunk to aggregate our logs, I’ll go look there!” Well, there were no error lines in the log that would indicate a back end database problem. Upon inquiring, I heard that since SQL Azure connection issues are a known and semi-frequent problem, logging of them is suppressed, since we have retry logic in place. I recommended that we log all failures, with ones that are going to be retried simply logged at a lower severity level like WARN, but ERROR on failures after the whole spread of retries. I declared this a showstopper bug that had to be fixed before release – not everyone was happy with that, but sometimes DevOps requires tough love.

I was disturbed that we could have periods of outage that were going unnoticed despite our investment in synthetic monitoring, pulling metrics, and searching logs. When I looked back at all our metrics over periods of known outage and they all looked good, I admit I became somewhat irate. We fixed it and I’m happy with our detection now, but I hope this is instructive in showing you how bad assumptions and not fully understanding the pros and cons of each instrumentation approach can end up leaving “stacked holes” that end up profoundly compromising your view of your service!

Filed under DevOps

DevOps Tip: Design for Failure

We have had some interesting internal discussions lately about application reliability. It’s probably not a surprise to many of you that the cloud is unreliable, on a small scale that is. Sure, on the large scale you use the cloud to make highly resilient environments. But a certain percentage of calls to the cloud fail – whether it’s Amazon’s or Azure’s management APIs, or hitting Amazon or Azure storage, or going through an Amazon ELB, or hitting SQL Azure. Heck, on Azure they plainly state that they will pull your instances out from under you, restart them, and move them to other hardware without notice. If you’re running 2 or more, they won’t do them all at the same time – so again, you get large scale resilience but at the cost of some small scale unreliability.

The problem is, that people sometimes come from the assumption that their application is always working fine, unless you can prove otherwise. This is fundamentally the wrong assumption. You have to assume your application has problems, unless you can prove it doesn’t. This changes your approach to testing, logging, and monitoring profoundly.

Take the all too common example of an app with intermittent failures. Let’s say it’s as bad as 1 in 20 times. 1 in 20 times a customer hits your application, it fails somehow. It is very likely you don’t know this. Because by default, you don’t know it. How would you? Well, obviously, by monitoring, logging, and testing. I’ll follow this up with a series of posts describing how and why those often fail to detect problems. The short form is that “ha ha, no they don’t.”

Here’s a bad story I’ll tell on myself. Here at NI, we rolled out a PDF instant quote generation widget. We have over 250 apps on ni.com, so we don’t put synthetic monitors on all of them (remind me to tell you about the time early at NI that I discovered synthetic monitoring was producing 30% of our site load). Apparently the logging wasn’t all that good either, it didn’t trigger any of our log monitoring heuristics. Anyway, come to find out later on that the app was failing in production about 75% of the time. This is an application on a “monitored” site, where a developer and a tester signed off on the app. Whoops. If you do a cursory test and assume it’ll work – well you know what they say about assumptions – they make an ass out of “you” and “mption.” 🙂

Anyway, to me part of the good part about the cloud is that they come out and say “we’re going to fail 2-5% of the time, code for it.” Because before the cloud, there were failures all the time too, but people managed to delude themselves into thinking there weren’t; that an application (even a complex Internet-based application) should just work, hit after hit, day after day, on into the future. So by having handling failure built in – like a lesser version of the Chaos Monkey – you’re not really just making your app cloud friendly, you’re making it better.

Real engineers who make cars and whatnot know better. That’s why there was a big ol’ maintenance hatch on the side of the Hubble Space Telescope; if any of you have watched the Hubble 3D IMAX film you get to see them performing maintenance on it. If a billion dollar telescope in fricking space has problems and needs to be maintainable, so does your little Web app.

But I see so many apps that don’t really take failure into account. Oh, maybe they retry some connections if they fail. But what if you get to the end of your retries? What if the response you get back is an unexpected HTTP code or unexpected payload? You’d think in the age of try/catch and easily integrated logging frameworks you wouldn’t see this any more, but I see it all the time. It’s a combination of not realizing that failure is ubiquitous, and not thinking about the impact (especially the customer facing impact) of that failure.

This is one of the (many) great DevOps learning experiences – Ops helping teach Devs all the things that can go wrong that don’t really go wrong much in a “frictionless” lab environment. “So, what do you do if your hard drive is suddenly not there?” (Common with Amazon EBS failures.) “What do you do if you took data off that queue and then your instance restarts before you put it into the database?” (Hopefully a transaction.) “What do you do if you can’t make that network connection, are you retrying every 5 ms and then filling up the system’s TCP connections?” (True story.) “Hey, I’m sure your app is pure as the driven snow right now, but is it always going to work the same when the PaaS vendor changes the OS version under you?”

In all circumstances, you should

- Plan for failure (understand failure modes, retry, design for it)

- Detect failure (monitor, log, etc.)

- Plan for and detect failure of your schemes to plan for and detect failure!

We do some security threat modeling here. I wonder if there’s not a lightweight methodology like that which could be readily adapted for reliability modeling of apps. Seems like something someone would have done… But a simple one, not like lame complicated risk matrices. I’ll have to research that.

Filed under DevOps

How We Do Cloud and DevOps: The Motion Picture

Our good friend Damon Edwards from dev2ops came by our Austin office and recorded a video of Peco and I explaining how we do what we do! Peco never blogs, so this is a rare opportunity to hear him talk about these topics, and he’s full of great sound bytes. 🙂

I apologize in advance for how much I say “right.”

Won’t somebody please think of the systems?

What is the goal of DevOps? If you ask a lot of people, they say “Continuous integration! Pushing functionality out faster!” The first cut at a DevOps Wikipedia article pretty much only considered this goal. Unfortunately, this is a naive view largely popular among developers who don’t fully understand the problems of service management. More rapid delivery and the practice of continuous integration/deployment is cool and it’s part of the DevOps umbrella of concerns, but it is not the largest part.

Let us review the concepts behind IT Service Management. I don’t like ITIL in terms of a prescriptive thing to implement, but as a cognitive framework to understand IT work, it’s great. Anyway, depending on what version you are looking at, there are a lot of parts of delivering a service to end users/customers.

- 1. Service Strategy (tie-guy stuff)

- 2. Service Design (including capacity, availability, risk management)

- 3. Service Transition (release and change management)

- 4. Service Operation (operations)

- 5. Continual Service Improvement (metrics)

Let’s concentrate on the middle three. Service transition (release) is where CI fits in. And that’s great. But most of the point of DevOps is the need for ops to be involved in Service Design and for the developers to be involved in Service Operation!

Service Transition

Sure, in the old waterfall mindset, service transition is where “the work moves from dev to ops.” Dev guys do everything before that, ops guys do everything after that, we just need a more graceful handoff. DevOps is not about trying to file some of the rough bits off the old way of doing things. It’s about improving service quality by more profoundly integrating the teams through the whole pipeline.

Here at NI, continuous integration was our lowest ranked DevOps priority. It’s a nice to have, while improving service design and operation was way, way more important to us. We’re starting work on it now, but consider our DevOps implementation to be successful without it. If you don’t have service design and operation nailed, then focusing on service transition risks “delivering garbage more quickly to users, and having it be unsupportable.”

Service Design

Services will not be designed correctly without embedded operational experience in their design and creation. You can call this “systems engineering” and say it’s not ops… But it’s ops. Look at the career paths if that confuses you. Our #1 priority in our DevOps implementation was to avoid the pain and problems of developing services with only input from functional developers. A working service is, more than ever, a synthesis of systems and applications and need to be designed as such. We required our systems architect and applications architect to work hand in hand, mutually design the team and tools and products, review changes from both devs and ops…

Service Operation

Services can not be operated correctly if thrown over the wall to an ops team, and they will not be improved at the appropriate rate. Developers need to be on hand to help handle problems and need to be following extremely closely what their application does in the users’ hands to make a better product. This was our #2 priority when implementing DevOps, and self service is a high implementation priority. Developers should be able to see their logs and production metrics in realtime so we put things like Splunk and Cloudkick in place and made their goal to not be operations facing, but developer facing, tools.

The Bottom Line

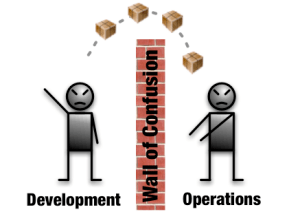

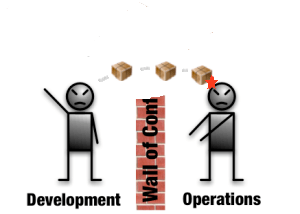

DevOps is not about just making the wall you throw stuff over shorter. With apologies to Dev2Ops,

|

|

Improvement? I think not!

To me the point of DevOps is to not have a wall – to have both development and operations involved in the service design, the transition, and the operation. Just implementing CI without doing that isn’t DevOps – it’s automating waterfall. Which is fine and all, but you’re missing a lot of the point and are not going to get all the benefits you could.

Filed under DevOps